(http://espn.go.com/blog/sweetspot/post/_/id/39162/burnett-martin-key-to-pirates-title-hopes)

In one of the biggest and most surprising moves of the early off-season, the Toronto Blue Jays signed catcher Russell Martin to a massive five year contract. Due in no small part to the sabermetric revolution, baseball has undergone a gradual but steady transition behind the scenes towards a more defensively conscious game. For Toronto, the signing of Martin was a flag in the sand type of moment. This is an organization who, while seemingly taking a more athletically focused approach in amateur talent acquisition, has consistently deployed an offense-oriented and defense-deficient roster at the major league level.

While Russell Martin was an outstanding hitter with Pittsburgh during the 2014 season (.290/.402/.430; 140 wRC+), such dynamic production has not been his calling card since his early-to-mid-twenties when he produced a 103, 122, and 112 wRC+ with the Dodgers from 2006 through 2008. During the five years in between, Martin’s adjusted offense was never more than 2% above average or 13% below average, which is more than acceptable for a catcher.

What made him his money is his work behind the plate. He’s always been known as a great defender, but he ascended to another level with Pittsburgh. Over the last two years, Martin allowed a total of 7 passed balls in 227 games, and caught 73 of 185 potential base stealers – roughly 40%. According to the Fielding Bible which measures defensive contributions based upon runs saved above or below average, Martin has been an average or better defender in seven of nine seasons while saving 58 total runs, with 28 of those coming over the last two.

Martin’s defensive excellence goes beyond just passed balls and caught base stealers; he’s also known as one of the game’s better pitch framers. In the public forum, pitch framing only truly caught on as a trendy topic in late 2011, when Mike Fast (then of Baseball Prospectus, now of the Houston Astros) derived a calculation which measured the net difference between strikes stolen and strikes lost by catchers and converted the number into a run equivalency. Fast’s study covered the 2007 through 2011 seasons, and during those five years Russell Martin produced the second most runs of any catcher in baseball via strike zone manipulation. His 15 runs per 120 games ranked fourth in baseball behind only Jose Molina, Jonathan Lucroy, and Gregg Zaun (!!).

The pack has closed the gap over the last few years, but Martin remains one of the premier framers. According to the website StatCorner, Martin’s framing was worth 17.0 runs in 2013 (6th) and an additional 11.7 runs in 2014 (10th). Comparatively, Dioner Navarro, the Blue Jays’ starting catcher last season, was worth -20.0 runs in the framing department in 2014, ranking third-last among 113 catchers measured.

While each catcher has his own mannerisms about how to frame pitches, the overall strategy is based around being as statuesque as possible behind the plate. A catcher who stabs his glove at pitches will receive far fewer borderline calls than the catcher who keeps his wrist still and receives the ball into his body. Another aspect is head calmness, as with the umpire crouched directly behind them, any required head movement to follow the pitch is drastically amplified. In June 2013, Russell Martin spoke to Baseball Prospectus’ Ben Lindbergh about his specific technique. Among the interesting quotes was Martin’s explanation as to why he gives the pitcher the location and then drops his glove during the delivery:

Lindbergh: It seems like you show the target for a second and then put your glove back down before the pitch.

Martin: To relax, yeah. I’m trying to get underneath the strike zone to where, when I do catch it, I can kind of bring it back up. Because if I give the target and leave the target here, and then the ball is down, if I go down to catch it, it looks like a ball. If I’m giving a target at the bottom of the zone, and I leave it there and I go down, it looks like a ball. If I give the target, relax my glove, come back and catch it up, it just gives the illusion of a strike.

When Lindbergh asked Martin about a pitch in which he set up high and away but the fastball drifted in over the plate for a called strike, the catcher offered an interesting perspective about high strikes, which will be followed up on later in this article:

It’s at the top of the zone, you just rarely get those high strikes. You get them sometimes when they’re right down the middle. If that ball’s away or in, we’re not getting that call. It’s just right down the middle, and it looks good. The umpire is right there, it’s right in front of his face, and he didn’t feel like it was high. And I’m sure he’s judging it like, anything under his mask is probably going to be close to a strike.

There’s one final aspect of catching which, while only loosely tied into pitch framing, has a unique importance of its own: game calling. Many young catchers receive the pitch-by-pitch game plan from the dugout, but established veterans like Martin are usually granted the freedom to devise and execute their own plan of attack. In an effort to determine if Martin has any obvious tendencies in terms of pitch preference and/or location, the Pitch F/X usage data from BrooksBaseball.net for A.J. Burnett and Francisco Liriano has been analyzed. Burnett was specifically chosen as he spent the 2012 season with the Pirates (but without Martin), the 2013 seasons with the Pirates and Martin, and the 2014 season with neither the Pirates nor Martin. On the other hand, Liriano split 2012 between the Twins and White Sox before joining Martin and the Pirates for both the 2013 and 2014 seasons.

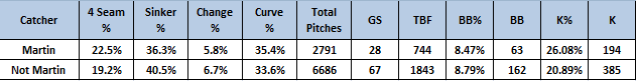

When Burnett pitched for the Blue Jays in the latter portion of the last decade, he was primarily a four-seam fastball, curveball, and changeup pitcher. In the years since he’s added a sinker to the repertoire. The table below summarizes Burnett’s pitch usage rate with and without Russell Martin behind the plate across the 2012, 2013, and 2014 seasons. At 28 starts with and 67 without, there’s a decent enough sample size from which to draw large-view conclusions.

With Martin behind the plate, Burnett threw a few more curveballs (+1.8%) and four-seam fastballs (+3.3%) at the expense of changeups (-0.9%) and sinkers (-4.2%), and while the usage numbers themselves aren’t overwhelmingly informative in either direction, the location data, particularly with two strikes, is. In the earlier quote from Martin, he spoke to the difficulty of getting high strikes called unless they’re dead center. The image below shows Burnett’s fastball location, with two strikes, in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

The 2013 frame is easily the most interesting (and Martin caught 28 of Burnett’s 30 starts that year, for the record), as it has a distinct presence up above the strike zone at the center of the plate – exactly where Martin suggested was the only place to get called third strikes high. In both 2012 and 2014, the uppermost third of the strike zone looks more like buckshot, with no clear or obvious plan of attack. The image below shows Burnett’s curveball location under the same two strike circumstances across the three seasons.

Once again, of the frames representing each of the three years, 2013 has the clearest sense of direction. Burnett’s two strike curveballs in 2012 and 2014 were consistently inconsistent. They finished all over the bottom half of the zone and below, and in 2014 in particular, missing up far more often than you’d like to see. With Martin behind the plate in 2013, Burnett was steady in pulling the curveballs down and away from right handed batters and at the back foot of lefties.

These minor changes in usage and approach appeared to pay major dividends. In the 28 starts Martin caught, Burnett struck out 26.08% of batters faced while walking just 8.47%. In the 67 non-Martin starts, Burnett was worse in both categories, striking out and walking 20.89% and 8.79% of batters faced respectively. A 5% difference may not sound like much, but in actuality that gap is enormous. In 2012, Burnett ranked a strong 30th among qualified starters in K-BB%. In 2013, he spiked to an incredible 12th, and in 2014, he plummeted down to 70th.

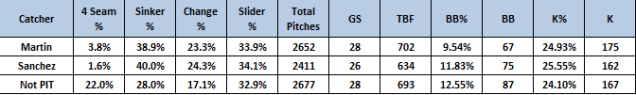

It wasn’t just Burnett who benefited from Martin’s presence behind the plate. After joining the Pirates in 2013, Francisco Liriano saw his four-seam fastball rate plummet and his sinker and changeup usage rates soar. It must be noted that some time after joining Pittsburgh, backup Tony Sanchez became Liriano’s “personal catcher”, which certainly adds an additional wrinkle to the mix. Even so, over the three years under the microscope, Martin caught 28 starts, Sanchez 26, and non-Pirate catchers 28, so once again there is sufficient enough data to reach some macro level conclusions. (It must also be noted that Liriano’s August 9th, 2013 start was removed from the sample as Brooks Baseball did not have pitch data for that game.)

In the non-Pirates starts in 2012, Liriano had a K-BB% rate of just 11.55%. With personal catcher Tony Sanchez, that number rose to 13.72%. With Russell Martin, it peaked at 15.39%. The strikeout rate was fairly consistent across the three catching situations with Sanchez coming out slightly ahead at 25.55%, but as we saw with Burnett, Martin does an excellent job of creating strikeouts while simultaneously limiting walks. Liriano’s 9.54% walk rate with Martin was significantly lower than the 11.83% and 12.55% rates with Sanchez and non-Pirates catchers, respectively.

One of the most interesting aspects of Liriano’s transformation lies with the slider. No earlier mention was made of changes in overall usage rate because across the three years it remained consistently between 33 and 34 percent of total pitches thrown, but it’s how and when the slider was thrown that is noteworthy. As evident in the image below, in 2012, Liriano had a typical slider heat map profile for a left handed pitcher. The image is from the catcher’s perspective, and shows an overwhelming number of sliders moving down and away from lefty batters, and/or at the back foot of righty batters. The images representing the 2013 and 2014 seasons show a drastically different trend, with sliders covering the entire bottom half of the zone.

My initial thought was that Liriano began using his slider as a modified cutter against left handed batters, but the greatest adjustment came against right handers with two strikes, as seen in the image below.

In 2012 with the Twins and White Sox, Liriano threw sliders almost exclusively at the back foot. In 2013, Liriano added a backdoor element to his slider, popping the outer corner on occasion while maintaining back foot dominance. Finally, in 2014, the plan of attack appeared to shift almost exclusively to the backdoor slider variety, as comparatively to the other years, Liriano barely went down and in whatsoever. How did right handed batters respond to this evolution? Against Liriano they had an overall wOBA of .340 in 2012, .310 in 2013, and just .284 in 2014.

Two pitchers is hardly enough data to draw meaningful conclusions, but there’s certainly enough evidence to suggest that Martin is cognizant of his pitcher’s best weapons and is capable of devising game plans that emphasize those strengths while sheltering any weaknesses.

Coming full circle, while undoubtedly a great skill to have, pitch framing alone might be dramatically understating the impact Martin could have on a pair of young Blue Jays pitchers still finding themselves in Aaron Sanchez and Drew Hutchison.

As an occasionally wild right hander possessing a dynamite fastball and devastating curve, Aaron Sanchez has more than a little in common with Burnett. The fact that Martin was able to quickly convince his veteran battery-mate to overhaul his approach for the better is an excellent sign for Blue Jays fans, as there’s absolutely no reason Sanchez shouldn’t be confounding batter after batter with the type of arsenal he possesses. Speaking specifically to the adjustments Burnett made with Martin, there’s no doubt Sanchez could use a few more high four-seam fastballs and down-and-out curveballs. Despite similarly electric stuff, batters made contact with 70.2% of the pitches they swung at outside the zone against Sanchez compared to just 61.9% for Stroman. If Martin’s adjustments could get Sanchez to Stroman or Hutchison’s (56.2%) level, the 22 year old top prospect could have a massively successful rookie season.

Speaking of Hutchison, he was swiftly and soundly demolished by left handed batters in 2014. Hutch features a changeup, but if his arsenal were a band, it would be the bass player whose name no one remembers as they fawn over the lead singer (fastball) and electric guitarist (slider). Specifically, left handers rode Hutch to the tune of a .353 wOBA, and while it’s expected that opposing managers will design their lineup with the best platoon advantage possible on any given night, that 56% of the batters Hutchison faced were lefties speaks volumes about the changeup’s respect level. In late October, Nick Ashbourne of Bluebird Banter spoke to the troubles Hutchison was having against lefties with the changeup, and planted the seed of the “sliders versus lefties” idea.

In a pair of January articles at Bluebird Banter and FanGraphs, the two writers spoke to the late season transformation that Hutchison made with his slider, lowering the velocity while adding significant vertical movement. The results were fairly jaw dropping, and both articles concluded that because of the changeup’s ineptitude, Hutchison might be far better off parking the pitch and whipping out this new and improved slider against lefties. Russell Martin’s successful contribution to transforming Francisco Liriano’s slider into an effective, backdoor weapon against opposite handed batters is another feather in the cap for Hutch’s 2015 prospects.

For a whole host of reasons Russell Martin is very likely to be the best catcher to ever play for the Toronto Blue Jays (not that it’s a particularly high benchmark), and in perhaps the most awkward sentence ever written, I’m tremendously excited to watch this man catch some balls. Is it Spring Training yet?

Great stuff. So far the new site has kicked ass.

LikeLike

Thanks for following, glad you’ve enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Awesome work!

LikeLike

Thanks, appreciate it.

LikeLike

Kyle you have some of the best writing / analysis I have seen on the Jays. I love the well reasearched arguments clearly and sucinctly stated, supported by excellent relevant graphical data. If you have an interest I suggest you apply for the Fangraphs position even if you only end up writing for them part-time.

LikeLike

I thought about it, but I think the position has been closed for further applications for a long time. I honestly feel that my work is at its best when I work on my own schedule and on topics I can choose after thinking about it for a couple of days. Being required to pump out 3 articles a week on other teams probably wouldn’t result in my best work. Plus, it’s really not a good fit given that most of my pieces run 2000-2500 words long haha. Not enough time in the day!

But thanks for the compliments!

LikeLike

Brad, many times when i read your posts, one phrase comes to mind and this is one of those times– grow up.

LikeLike

Love the sweater and those denim accessories!

LikeLike

Transit TV generated very little revenue for Metro – maybe the cost of a bus a year. I would rather pay an extra five or ten cents per trip than listen to that annoyance. Good riddance, even if I did enter a contest occasionally.

LikeLike

Full Article https://hydra2020gate.com

LikeLike